Lincoln’s colossal mourning became a kind of mania. There is a germ of historical truth that serves as the foundation of the entire novel (O.K., it is a novel). The emotion overflows the style the second-person accounts become more poignant than any first-person testimony could possibly be. Rather-and this is true of much of the book-it is because the constraints of the antique diction Saunders gives his characters, as well as the overly cautious respect that chroniclers afforded Lincoln in the contemporaneous historical excerpts, are not enough to hold back the enormity of feeling Lincoln evoked in those writers who watched him mourn. This is not because Saunders puts so many sorrowful words into Lincoln’s mouth.

The portrait of the president-acutely aware that through the war he is visiting on hundreds of thousands the almost unbearable grief he is feeling himself-is so monumentally sorrowful it will cause the reader to rest the book on his or her chest and take a breath.

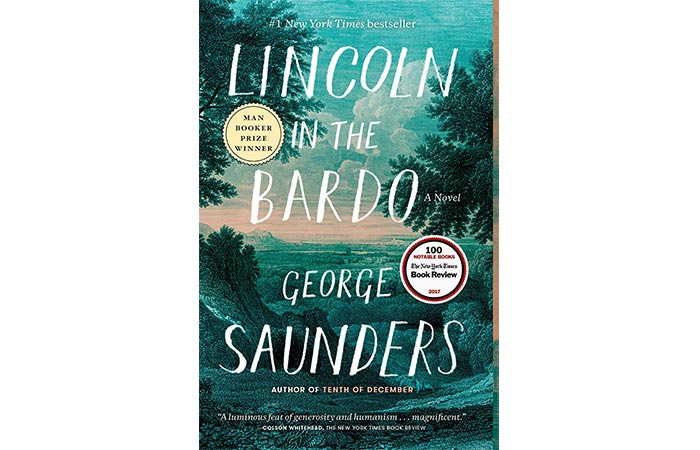

No one feels this more than his father, nor mourns him harder. The reader will actively mourn Willie, who was by all accounts a gentle, mischievous, sweet-natured boy who died far too young. Willie, as someone recalls (from among the many chunks of actual historical writing Saunders plucks from American literature’s ocean of Lincoln-iana, and scatters throughout the book), was the kind of child people imagine their children will be. Photograph of William "Willie" Wallace Lincoln. The Bardo-the term is Tibetan for the place, or space, between life and its aftermath-is in this case a Washington, D.C., cemetery circa 1862, occupied by, among others, Willie Lincoln, the president’s beloved 11-year-old son, who died of typhoid fever not long after his father started waging his Civil War. The book boasts a Bruegel-esque array of characters-refined, vulgar, saintly, criminal-but the Lincoln of the title is, no surprise, the 16th president of the United States. The uncertain souls involved have to come to terms with what we readers know from the start, and which is no small matter: They are not “sick,” as they keep insisting. Conventional thinking-though Lincoln in the Bardo is anything but conventional-says that characters in a novel have to grow, learn, to experience some kind of epic realization. But on second thought, or third, perhaps it is a novel.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)